A lot of speculators have second and third homes – things like vacation homes that are rarely used and make no sense economically.

I’d be impressed if they’ve appreciated by more than inflation. That would mean if you built a new house on that lot for the same cost (inflation-adjusted) as you built the original house, it would be worth less that the current 40y old house.

Thats a very small % of the housing stock.

And vacation homes are really not in the same market as the rest of the housing market.

If someones lake house loses speculative value and they dump it then that won’t have much impact on the cost of houses in / near town.

I am not necessarily claiming that they have appreciated much more than inflation. But it does depend a lot on building costs and the local market/region.

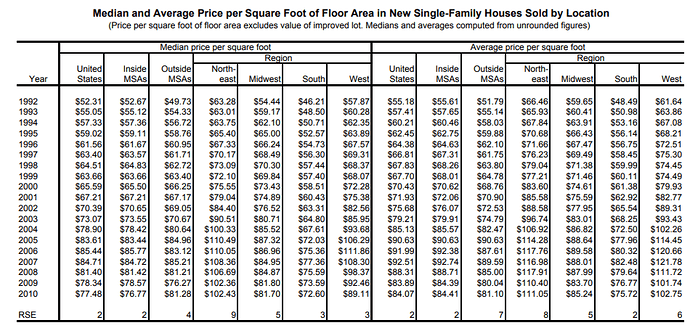

https://www.census.gov/const/C25Ann/soldmedavgppsf.pdf

This chart pretty much proves my point.

This says that overall, in the US, the median value of new houses has not even quite kept up with inflation ($52.31 in 1992 is worth $80.08 in 2010). So, clearly, a newly-built house in 1992, that’s now 18yrs old in 2010, would fare even worse.

Sure, some subsets in that chart have slightly beat inflation, but not nearly enough to account for the difference in value between a new house and a 20 year old house.

I thought your original point was that houses DON’T appreciate. Then it became, they don’t appreciate more than inflation, to which I replied that I agree, but it depends on the market. That chart doesn’t prove anything related to those points because it is about NEW houses.

I actually posted that chart to point out the cost of new construction. Your other point was that a new home on specific land wouldn’t be cheaper than an old home on the same land. I agree and that chart shows that new construction costs have mostly kept in line with inflation (with fluctuations around the housing boom/bust - I wish we had the next 8 years of data), but that doesn’t mean new home costs have. The reason for that is because new homes today are 1,000 square feet larger than they were 40 years ago. People simply can’t buy new small homes anymore and that is helping older homes appreciate.

I guess my overall point is that homes have appreciated in large part because home building costs increase similar to inflation, but home builders don’t build the same type of homes they used to. I believe 40 years from now, the 2600 sq ft homes will not have appreciated nearly as much as the 1700 sq ft homes did for the past 40 years simply because the size of the avg home can’t increase by 1000 sq ft over the next 40 years. Then again, the shortage of skilled labor (noted in another FD thread) may increase the price per sq ft of new construction.

Regardless, I don’t think you and I have a fundamental disagreement on home prices.

Semantics then. If something “appreciates” less than inflation, it is a depreciating asset. It is decreasing in value relative to everything else.

I see your point regarding the relative value of different types and sizes of houses. But even if 1700sqft homes appreciate faster than 2600sqft homes, they will still appreciate less than inflation. Which means, regardless of the potential future desirability of a house, you are better off simply buying the land, and sticking your remaining money into an inflation-protected asset. (Setting aside the present and ongoing utility of the house obviously.)

I suppose you’re right about it being semantics. But in that sense, what is an appreciating asset? When I think about assets people use everyday, I think in terms of things like cars (depreciating asset) and homes (appreciating asset). To put a car and a home in the same asset category would be incorrect, imo.

Sure, but who sets aside the present and ongoing utility of the house? I guess I just consider houses appreciating assets because I can’t really think of anything else that someone uses every day for decades, and then sells it and walks away with more money than they started. If that’s not the definition of appreciating asset, I’m just not sophisticated enough to talk about assets.

But I think you only think about homes as an appreciating asset because of land appreciation. I think if you could easily separate your house value from your land value, it would be more obvious that the house is actually quite similar to the car. Both have current utility, but both have a limited lifetime and thus decrease in value over time and require constant maintenance.

Cars also depreciate much more quickly of course, which makes it easier to see the depreciation, since it’s happening even in nominal terms. Whereas the house may only be depreciating in real (inflation-adjusted) terms.

I don’t think it’s incorrect to consider a car and a house (but not the land) in the same category. I think it adds perspective to real estate purchases, and helps avoid getting caught up in assumptions that they will always appreciate.

But why would you treat buildings and land as separate entities when they are virtually permanently tied together?

Whats it really going to gain if you think of them separately?

Yes real estate doesn’t always go up. We should be aware of that regardless.

Just to better understand what you’re buying.

I think the main reason I disagree with you on this is because I work in local government and agree with how real estate is assessed by local governments. I just looked at the historical real estate assessment of my home. Using the dates 1992-2010 (from the other chart), my land has gone up in value by 67% and my structure has gone up by 56%. Following your theory, do you think my land actually went up by 83% and my structure went up 0%? Did the structure increase in value at all from when it was built in 1987 for $58,000? Or, like a car, would you say it went down in value?

To put it another way, If my house mysteriously disappeared off my property tomorrow (the only way of separating land from structure as you say I should do), I am confident that the value of what I own would go down by A LOT more than $58,000. I am pretty sure if I had to sell my lot after my house disappeared, I would get an amount much closer to what my land is assessed at and not what my total property assessment is.

Car engines might appreciate better than the sheet metal cars are made out of.

Should we track car engine values separate??

You need to de-inflate these numbers to have any understanding of what’s going on. Inflation from 1992 to 2010 was 54.46%. So, in fact, your structure has increased in real terms by only 1%. Your land has increased by about 8%. I think this paints a far clearer picture of your purchase.

The fact that your house hasn’t depreciated significantly in real terms (by these numbers), may be related to your thoughts on relative availability of the particular size or type of house. Though really, I’m a little skeptical; I suspect there’s a decent margin of error in this kind of assessment.

You are right. It should go down by somewhat less than $124,000, which is the inflation-adjusted cost to build (58k adjusted from 1987 to 2017).

You’ll just have to take my word for it because I don’t plan on giving out enough information for you to check up on my home’s actual location. According to lot prices near my neighborhood, your $124,000 estimate is off by quite a bit. You really should rethink your conclusions on this.

To the extent that the drive-train and engine are a good proxy for the reliability of a car, I think this is fairly reasonable, and people do it intuitively. Older cars are mostly valued on their expected reliability. Newer cars are valued more on finishes and features. These two things have very different depreciation rates, and this fact is why many on here will say it’s more financially prudent to buy older cars.

(Sheet metal is a negligible cost of most cars though, so not really a consideration.)

So, you’re saying it would cost more than $124,000 to build a house equivalent to yours in your area?

Yup, the error is that the land is likely worth less than what it is assessed at and the structure is worth more. Either way, my home has kept up with inflation. It is NOT a depreciating asset. I would say that is the case with enough single family homes in the US to argue that it is improper to say that homes, generally speaking, are depreciating assets.

Yes. You could get a double wide manufactured home for that much though. ![]()

I can’t comment on your house specifically, but I just don’t see how you can believe this applies generally.

Do you agree that the building cost, generally speaking, of a new house roughly increases by inflation? (The chart you posted certainly seems to say this.)

Do you agree that a newly built house is generally worth significantly more than the same house built 20+ years ago?

Those two facts alone mean that houses, in general, cannot keep up with inflation.