Those appear to now be non-existent in the couple of FL’s that I stop at … when there’s Cherry Coke on sale. ![]()

Why do these supposedly geniuses of macroeconomics seem to always lag common sense opinion? Whether it’s to raise or lower interest rates, they always seem to only act once the shit hits the fan and everyone is screaming for intervention. Aren’t they supposed to be a bit better at this than a bunch of trolls on a finance board?

I would not otherwise have intervened with a response, but I am forced to do so owing to the above obvious reference to my membership group:

While the Fed’s putative goal, and task, relates to employment rate enhancement and defense of the dollar’s purchasing power, that’s not reality. Their de facto numero uno goal is support of equity prices. Period.

It is tough to foster equity price support while simultaneously raising interest rates. Even the smartest finance board trolls would be hard pressed to accomplish that.

We finance board trolls, whether singly or jointly, have our limitations. ![]()

Looking for your lost package delivery? CA criminals aren’t helping.

https://mobile.twitter.com/johnschreiber/status/1481770722271760384

Uh, what kind of fishing lures? ![]()

ETA: Maybe this is what happened to my dog’s DNA test. ![]()

(the below shamelessly stolen from the Wall Street Journal)

Bond markets are not signalling runaway inflation

There are good reasons to believe that today’s hot economy may be just a temporary respite

By Greg Ip

Jan. 14, 2022 5:30 am ET

With the best job growth in over 40 years, inflation a national obsession and the Federal Reserve preparing to raise interest rates, it is easy to forget how different the world was before the pandemic. The global environment then was marked by sluggish growth, lackluster investment, worryingly low inflation and low interest rates.

Which could be where the U.S. is headed again.

The bond market seems to be betting on it. Even with U.S. inflation at a near-40 year high of 7%, 10-year Treasury yields are below 2%. Real bond yields—that is, adjusted for expected future inflation—are negative 0.2%, and have been mostly negative since the start of the pandemic, only the second such episode in 30 years.

Even as the Fed moves up plans to raise interest rates, markets have revised down how high they are likely to get. They see the federal-funds rate, now near zero, reaching only 2% in 2025, which would be slightly negative in real terms.

Investors, of course, may simply be wrong. Since the start of the year, investors appear to have reassessed the interest-rate outlook. Bonds have sold off, with the 10-year Treasury yield, which moves in the opposite direction to its price, jumping to 1.7% from 1.5% at the end of 2021.

Yet there are good reasons to think today’s sizzling economy may be just a temporary respite. Looked at over the longer term, real yields have been declining for decades. Olivier Blanchard, the former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund, makes this point in a new book, “Fiscal Policy Under Low Interest Rates.” In it he notes that safe interest rates—in other words, those on risk-free government debt—have been declining in the U.S., Western Europe, and Japan for 30 years. “Their decline is due neither to the Global Financial Crisis of the late 2000s, nor to the current Covid crisis, but to more persistent factors,” he writes. “Something has happened in the last 30 years, which is different from the past.”

Several years ago, former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers argued a persistent shortfall of investment amid a glut of global savings was holding down both growth and interest rates, a situation he called “secular stagnation,” a term first used in the 1930s.

“Secular stagnation was the issue of the moment in the late 1930s,” Mr. Summers said at The Wall Street Journal’s CEO Council Summit in December. “Once rearmament and World War II began, and there was a massive fiscal expansion, it was no longer the issue. In the same way, after we’ve had a 15%-of-GDP fiscal expansion, secular stagnation is not the issue of this moment.”

- New warnings*

That is why early last year Mr. Summers switched from warning about secular stagnation to warning that fiscal and monetary stimulus threatened to send inflation sharply higher. Yet he thinks it more likely than not that secular stagnation will return in a few years’ time: That is a “natural interpretation” of why markets expect real interest rates to remain so low, he said.

This possibility also weighs on the minds of Fed officials. Neel Kashkari, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, said in supporting higher rates this year that he is weighing two opposing risks. One is that high inflation becomes embedded in the public’s behavior, which would require even higher interest rates later on. The other is that after Covid-19 passes, the world returns to the pre-pandemic regime of low growth and low inflation. That regime, he wrote on the publishing site Medium, was driven by “demographics, trade, and technology factors. It is unlikely that these underlying forces have gone away.”

Slower population growth reduces demand for cars, houses and other durable goods, and the need for business to expand capacity. Lengthened life expectancy means people spend more of their lives retired, so they save more in anticipation. In combination, these effects tend to hold down interest rates.

The pandemic intensified the trend of slowing population growth around the world. The U.S. population grew just 0.1% in the year to July—the slowest on record—as both birthrates and immigration plummeted. With retirements accelerating because of the pandemic, the U.S. labor force ended last year 1.4% smaller than before the pandemic.

China’s population barely rose in 2020, and its population in the 15 to 59 age range shrank 5% in the preceding decade. The government has responded with alarm. A state-backed newspaper briefly urged Communist Party members to have more children, and access to vasectomies and abortion has reportedly diminished.

- A hit to productivity*

Apart from population, the main contributor to growth is productivity, and that too appears to have suffered during the pandemic. While businesses stepped up digitization by investing more in e-commerce, cloud computing and artificial intelligence, productivity has still suffered because of Covid-19 protocols and restrictions, and sweeping changes in where, and whether, people chose to work. The recent rise in inflation suggests the U.S. can’t grow as fast as before without straining productive capacity. Some of those barriers to growth are likely to persist even after the pandemic passes.

Meanwhile, Chinese investment has slowed under the impact of its own Covid-19 restrictions and cooling property sector. As a result, its excess savings are once again being recycled to the rest of the world. One indicator of that excess, China’s trade surplus, rose 53% in the 12 months through November to $673 billion from two years earlier. Those surpluses are apt to continue if a shrinking labor force and reduced property investment continue to weigh on Chinese domestic demand.

A return to a low-growth, low-inflation, low-interest-rate world has a positive side. It would mean rich asset valuations are less likely to represent a bubble. Stocks are trading at near-record price-earnings ratios, but those ratios are justifiable if real interest rates remain around zero. Federal debt, which since 2019 has shot from 80% to around 100% of GDP, is more easily sustained with low rates, although slower growth works in the opposite direction. Indeed, one reason interest rates may be low is that investors think the Fed won’t raise them so much for fear of a stock market crash. It raised rates above 2.25% in 2018, then reversed course when stock and commodity markets wobbled.

What if investment and economic growth weaken, but inflation stays high? If inflation settles at, say, 3.5%, as some economists expect, then bond yields could also double to 3.5% with real rates remaining zero. In the U.S., though, high and volatile inflation eventually led to higher real interest rates, while in other countries such as Japan, stagnant growth and low inflation have gone hand in hand.

For now, investors think inflation is coming down, and will average 2.5% over the next 10 years, based on the yields on regular and inflation-indexed bonds. But Joe Gagnon, an economist at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, warns: “Bond markets have never predicted an outburst of inflation. So why would we think they can now?” He adds: “They respond very quickly when inflation starts to rise.”

While the Fed’s putative goal, and task, relates to employment rate enhancement and defense of the dollar’s purchasing power, that’s not reality. Their de facto numero uno goal is support of equity prices.

These are the only two options isn’t it? They’re either incredibly bad at their job considering their qualifications, or IF we assume that’s not the case, the only other possibility is that they’re just doing a different job than we think they’re mandated to do. That’s a fair conclusion.

On the other hand, this assumption of competence and having different unofficial goal of propping the stock market, is somewhat at odds with their track record. I know hindsight is 20/20 but looking back at the Great Recession of 2007, they did not exactly cover themselves in glory with their predictive capabilities or response. And that did have rather negative short-term consequences for the stability of equity prices in 2007-2008 which would be contrary to that assumed unofficial goal.

Strictly personally speaking, I wouldn’t mind them doing all they can to support equity prices since I suspect that, on the balance, it’ll help me more than them looking out for main street, but I cannot help but question whether their actions are deliberate in propping them, or merely incidental due to incompetence or lack of leadership (aka balls).

Mountain Dew Zero Sugar has been straight up non-existent in my area for months. It’s quite popular, so I’m not sure what the hell is wrong with my local Pepsi bottler.

Yellen: Don’t worry. Be happy. Tomorrow is only a day away.

Janet Yellen, sagacious as they come where inflation is concerned, sees an end to our inflation concerns coming. Please be patient:

Yellen Says Substantial Inflation Slowdown Expected Next Year

Ya say you’re poor and the soup is getting thin and the kids need shoes and the rent is overdue? Is that what’s happening for you, bucky? Well, cheer up! Just wait a year and if you’re still alive Yellen is promising an end to your misery. Ain’t that wonderful? Until then take off those old shoes and boil up the leather and try to make better soup. Cause for the next year Yellen has nothing for you whatsoever.

Well duh we told you already! It’s only transitory. You know, like our presence on Earth… So it’ll be fine.

So now the Treasury is adding their assurance that t̶h̶e̶ ̶v̶a̶c̶c̶i̶n̶e̶ inflation is perfectly safe and e̶f̶f̶e̶c̶t̶i̶v̶e̶ transitory. And as each of you have alluded, Jimmy Carter’s inflation was transitory, too.

And like Biden’s will be, and their political careers likewise.

How’s that supply chain going up north? Biden banned unvaxxed truckers from crossing the border, despite a shortage of truckers generally. Kinda like banning the healthy unvaxxed nurses from working in busy hospitals while making the vaxxed ones with covid show up and work anyway.

Of course a negative test isn’t acceptable because it’s not about public health, it’s about the vaccine religion. Also, of course illegal immigrants are welcome without being vaccinated.

That is axiomatic with the Biden regime. You didn’t even have to mention it. ![]()

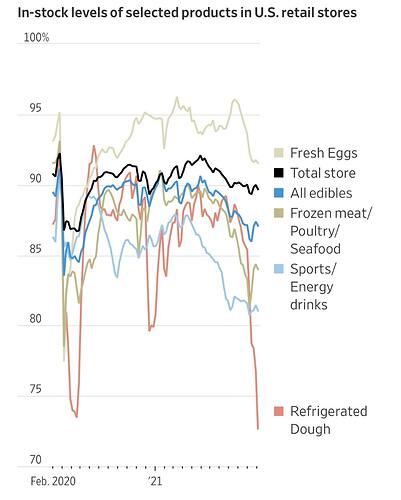

Looking at total store in-stock levels, the needle has not moved much since we came out of the lockdown, staying around 90% the whole time with ups and downs looking linked with COVID waves. All edibles is not on a good trend though which may be what gets people upset lately. Still it’s moved from around 90% pre-pandemic to about 87% now. That’s seems like a far cry from the doom picture of abundance of completely empty stores.

Went shopping to 3 different stores over the weekend (restocking before a snow storm) and I did not experience any noticeable lack of supplies at any of them. Maybe these stores are fine since they are right off the interstate so easily supplied. YMMV I guess.

Pre-pandemic, the only “shortages” we ever came across was the occasional time that the store would run out of something on-sale near the end of the sale - usually a popular cut of beef or chicken. Now it is common to see no sales on popular cuts, and even when those cuts are full price, sometime nothing in the meat case. Produce departments regularly run out of things. No “bare shelves” but definitely low or no stock on lots of popular items like juice boxes, sports drinks, and chips. For the first time I’ve ever seen in my life, we’re now having fewer options on pasta in stock. To me, 3% shouldn’t be a noticable difference. If pre-pandemic, we were at 90% (it felt like we were at 97%), then in this region at least, depending on the week we’re ranging between 82-70%.

I’m thinking about grocery stocked shelves as not being a real problem anymore. It’s something that we can manage easily enough. After all we are not in a third world country.

I filled my car with gasoline yesterday. A job that was annoying, but a necessity. Almost empty, and the price seemed to be a little lower than the last filling. $4.79, I may be forgetting, but it seems like closer to $5 a gallon last time. So better!!

Our shelve have gotten rather bare over the past week, but that’s weather related more than anything.

Frozen potatoes (french fries), frozen pizza, and frozen pre-cooked chicken (like chicken tenders) remain our categories with supply issues unrelated to the weather. And Gatorade/Powerade.